Standards & History

The Standard of the Australian Cattle Dog

GENERAL APPEARANCE - The general appearance is that of a strong compact, symmetrically built working dog, with the ability and willingness to carry out his allotted task however arduous. Its combination of substance, power, balance and hard muscular condition must convey the impression of great agility, strength and endurance. Any tendency to grossness or weediness is a serious fault.

CHARACTERISTICS - As the name implies the dog's prime function, and one in which he has no peer, is the control and movement of cattle in both wide open and confined areas. Always alert, extremely intelligent, watchful, courageous and trustworthy, with an implicit devotion to duty making it an ideal dog.

TEMPERAMENT - The Cattle Dog's loyalty and protective instincts make it a self-appointed guardian to the Stockman, his herd and his property. Whilst naturally suspicious of strangers, must be amenable to handling, particularly in the Show ring. Any feature of temperament or structure foreign to a working dog must be regarded as a serious fault.

HEAD AND SKULL - The head is strong and must be in balance with other proportions of the dog and in keeping with its general conformation. The broad skull is slightly curved between the ears, flattening to a slight but definite stop. The cheeks muscular, neither coarse nor prominent with the underjaw strong, deep and well developed. The foreface is broad and well filled in under the eyes, tapering gradually to form a medium length, deep, powerful muzzle with the skull and muzzle on parallel planes. The lips are tight and clean. Nose black.

EYES - The eyes should be of oval shape and medium size, neither prominent nor sunken and must express alertness and intelligence. A warning or suspicious glint is characteristic when approached by strangers. Eye colour, dark brown.

EARS - The ears should be of moderate size, preferably small rather than large, broad at the base, muscular, pricked and moderately pointed neither spoon nor bat eared. The ears are set wide apart on the skull, inclining outwards, sensitive in their use and pricked when alert, the leather should be thick in texture and the inside of the ear fairly well furnished with hair.

MOUTH - The teeth, sound, strong and evenly spaced, gripping with a scissor-bite, the lower incisors close behind and just touching the upper. As the dog is required to move difficult cattle by heeling or biting, teeth which are sound and strong are very important.

NECK - The neck is extremely strong, muscular, and of medium length broadening to blend into the body and free from throatiness.

FOREQUARTERS - The shoulders are strong, sloping, muscular and well angulated to the upper arm and should not be too closely set at the point of the withers. The forelegs have strong, round bone, extending to the feet and should be straight and parallel when viewed from the front, but the pasterns should show flexibility with a slight angle to the forearm when viewed from the side. Although the shoulders are muscular and the bone is strong, loaded shoulders and heavy fronts will hamper correct movement and limit working ability.

BODY - The length of the body from the point of the breast bone, in a straight line to the buttocks, is greater than the height at the withers, as 10 is to 9. The topline is level, back strong with ribs well sprung and carried well back not barrel ribbed. The chest is deep, muscular and moderately broad with the loins broad, strong and muscular and the flanks deep. The dog is strongly coupled.

HINDQUARTERS - The hindquarters are broad, strong and muscular. The croup is rather long and sloping, thighs long, broad and well developed, the stifles well turned and the hocks strong and well let down. When viewed from behind, the hind legs, from the hocks to the feet, are straight and placed parallel, neither close nor too wide apart.

FEET - The feet should be round and the toes short, strong, well arched and held close together. The pads are hard and deep, and the nails must be short and strong.

TAIL - The set on of tail is moderately low, following the contours of the sloping croup and of length to reach approximately to the hock. At rest it should hang in a very slight curve. During movement or excitement the tail may be raised, but under no circumstances should any part of the tail be carried past a vertical line drawn through the root. The tail should carry a good brush.

GAIT/MOVEMENT - The action is true, free, supple and tireless and the movement of the shoulders and forelegs is in unison with the powerful thrust of the hindquarters. The capability of quick and sudden movement is essential. Soundness is of paramount importance and stiltiness, loaded or slack shoulders, straight shoulder placement, weakness at elbows, pasterns or feet, straight stifles, cow or bow hocks, must be regarded as serious faults. When trotting the feet tend to come closer together at ground level as speed increases, but when the dog comes to rest he should stand four square.

COAT - The coat is smooth, a double coat with a short dense undercoat. The outer-coat is close, each hair straight, hard, and lying flat, so that it is rain-resisting. Under the body, to behind the legs, the coat is longer and forms near the thigh a mild form of breeching. On the head (including the inside of the ears), to the front of the legs and feet, the hair is short. Along the neck it is longer and thicker. A coat either too long or too short is a fault. As an average, the hairs on the body should be from 2.5 to 4 cms (approx. 1-1.5 ins) in length.

COLOUR -

Blue - The colour should be blue, blue-mottled or blue speckled with or without other markings. The permissible markings are black, blue or tan markings on the head, evenly distributed for preference. The forelegs tan midway up the legs and extending up the front to breast and throat, with tan on jaws; the hindquarters tan on inside of hin y are permissible but not desirable.

Red Speckle - The colour should be of good even red speckle all over, including the undercoat, (neither white nor cream), with or without darker red markings on the head. Even head markings are desirable. Red markings on the body are permissible but not desirable.

SIZE -

Height: Dogs 46-51 cms (approx. 18-20 ins) at withers

Bitches 43-48 cms (approx. 17-19 ins) at withers

FAULTS - Any departure from the foregoing points should be considered a fault and the seriousness with which the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion to its degree.

NOTE - Male animals should have two apparently normal testicles fully descended into the scrotum.

The Standard of the Australian Kelpie

GENERAL APPEARANCE - The general appearance shall be that of a lithe, active dog of great quality, showing hard muscular condition combined with great suppleness of limb and conveying the capability of untiring work. It must be free from any suggestion of weediness.

CHARACTERISTICS - The Kelpie is extremely alert, eager and highly intelligent, with a mild, tractable disposition and an almost inexhaustible energy, with marked loyalty and devotion to duty. It has a natural instinct and aptitude in the working of sheep, both in open country and in the yard. Any defect of structure or temperament foreign to a working dog must be regarded as uncharacteristic.

TEMPERAMENT - (See under characteristics)

HEAD AND SKULL - The head is in proportion to the size of the dog, the skull slightly rounded, and broad between the ears. The forehead running in a straight profile towards a pronounced stop. The cheeks are neither coarse nor prominent, but round to the foreface, which is cleanly chiselled and defined. The muzzle, preferably slightly shorter in length than the skull. Lips tight and clean and free from looseness. The nose colouring conforms to that of the body coat. The overall shape and contours produce a rather fox-like expression, which is softened by the almond-shaped eyes.

EYES - The eyes are almond shaped, of medium size, clearly defined at the corners, and show an intelligent and eager expression. The colour of the eyes to be brown, harmonising with the colour of the coat. In the case of blue dogs a lighter coloured eye is permissible.

EARS - The ears are pricked and running to a fine point at the tips, the leather fine but strong at the base, set wide apart on the skull and inclining outwards, slightly curved on the outer edge and of moderate size. The inside of the ears is well furnished with hair.

MOUTH - The teeth should be sound, strong and evenly spaced, the lower incisors just behind but touching the upper, that is a scissor bite.

NECK - The neck is of moderate length, strong, slightly arched, gradually moulding into the shoulders, free from throatiness and showing a fair amount of ruff.

FOREQUARTERS - The shoulders should be clean, muscular, well sloping with the shoulder blades close set at the withers. The upper arm should be at a right angle with the shoulder blade. Elbows neither in nor out. The forelegs should be muscular with strong but refined bone, straight and parallel when viewed from the front. When viewed from the side, the pasterns should show a slight slope to ensure flexibility of movement and the ability to turn quickly.

BODY - The ribs are well sprung and the chest must be deep rather than wide, with a firm level topline, strong and well-muscled loins and good depth of flank. The length of the dog from the forechest in a straight line to the buttocks, is greater than the height at the withers as 10 is to 9.

HINDQUARTERS - The hindquarters should show breadth and strength, with the croup rather long and sloping, the stifles well turned and the hocks fairly well let down. When viewed from behind, the hind legs, from the hocks to the feet, are straight and placed parallel, neither close nor too wide apart.

FEET - The feet should be round, strong, deep in pads, with close knit, well arched toes and strong short nails.

TAIL - The tail during rest should hang in a very slight curve. During movement or excitement it may be raised, but under no circumstances should the tail be carried past a vertical line drawn through the root. It should be furnished with a good brush. Set on position to blend with sloping croup, and it should reach approximately to the hock.

GAIT/MOVEMENT - To produce the almost limitless stamina demanded of a working sheepdog in wide open spaces the Kelpie must be perfectly sound, both in construction and movement. Any tendency to cow hocks, bow hocks, stiltiness, loose shoulders or restricted movement weaving or plaiting is a serious fault. Movement should be free and tireless and the dog must have the ability to turn suddenly at speed. When trotting the feet tend to come closer together at ground level as speed increases but when the dog comes to rest it stands four square.

COAT - The coat is a double coat with a short dense undercoat. The outercoat is close, each hair straight, hard, and lying flat, so that it is rain-resisting. Under the body, to behind the legs, the coat is longer and forms near the thigh a mild form of breeching. On the head (including the inside of the ears), to the front of the legs and feet, the hair is short. Along the neck it is longer and thicker forming a ruff. The tail should be furnished with a good brush. A coat either too long or too short is a fault. As an average, the hairs on the body should be from 2 to 3 cms (approx. 0.75 - 1.25 ins) in length.

COLOUR - Black, black and tan, red, red and tan, fawn, chocolate, and smoke blue.

SIZE - Height: Dogs 46-51 cms (approx. 18-20 ins) at withers Bitches 43-48 cms (approx. 17-19 ins) at withers

FAULTS - Any departure from the foregoing points should be considered a fault and the seriousness with which the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion to its degree.

NOTE - Male animals should have two apparently normal testicles fully descended into the scrotum.

The Standard of the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog

GENERAL APPEARANCE - Shall be that of a well proportioned working dog, rather square in profile with a hard-bitten, rugged appearance, and sufficient substance to convey the impression of the ability to endure long periods of arduous work under whatsoever conditions may prevail.

CHARACTERISTICS - The "Stumpy" possesses a natural aptitude in the working and control of cattle, and a loyal, courageous and devoted disposition. It is ever alert, watchful and obedient, though suspicious of strangers. At all times it must be amenable to handling in the Show ring.

TEMPERAMENT - (See under characteristics)

HEAD AND SKULL - The skull is broad between the ears and flat, narrowing slightly to the eyes with a slight but definite stop. Cheeks are muscular without coarseness. The foreface is of moderate length, well filled up under the eye, the deep powerful jaws tapering to a blunt strong muzzle. Nose black, irrespective of the colour of the dog.

EYES - The eyes should be oval in shape, of moderate size, neither full nor prominent, with alert and intelligent yet suspicious expression, and of dark brown colour.

EARS - The ears are moderately small, pricked and almost pointed. Set on high yet well apart. Leather moderately thick. Inside the ear should be well furnished with hair.

MOUTH - The teeth are strong, sound and regularly spaced. The lower incisors close behind and just touching the upper. Not to be undershot or overshot.

NECK - The neck is of exceptional strength, sinuous, muscular and of medium length, broadening to blend into the body, free from throatiness.

FOREQUARTERS - The shoulders are clean, muscular and sloping with elbows parallel to the body. The forelegs are well boned and muscular. Viewed from any angle they are perfectly straight.

BODY - The length of the body from the point of the breast-bone to the buttocks should be equal to the height of the withers. The back is level, broad and strong with deep and muscular loins, the well sprung ribs tapering, to a deep moderately broad chest.

HINDQUARTERS - The hindquarters are broad, powerful and muscular, with well developed thighs, stifles moderately turned. Hocks are strong, moderately let down with sufficient bend. When viewed from behind the hind legs from hock to feet are straight, and placed neither close not too wide apart.

FEET - The feet should be round, strong, deep in pads with well arched toes, closely knit. Nails strong, short and of dark colour.

TAIL - The tail is undocked, of a natural length not exceeding four inches, set on high but not carried much above the level of the back.

GAIT/MOVEMENT - Soundness is of paramount importance. The action is true, free, supple and tireless, the movement of the shoulders and forelegs in unison with the powerful thrust of the hindquarters. Capability of quick and sudden movement is essential. Stiltiness, cow or bow hocks, loaded or slack shoulders or straight shoulder placement, weakness at elbows, pasterns or feet, must be regarded as serious faults.

COAT - The outer coat is moderately short, straight, dense and of medium harsh texture. The undercoat is short, dense and soft. The coat around the neck is longer, forming mild ruff. The hair on the head, legs and feet, is short.

COLOUR - Blue - The dog should be blue or blue mottled, whole coloured. The head may have black markings. Black markings on the body are permissible.

Red Speckle - The colour should be a good even red speckle all over, including the undercoat (not white or cream), with or without darker, red markings on the head. Red patches on the body are permissible.

SIZE - Height: Dogs 46-51 cms (18-20 ins) at withers Bitches 43-48 cms (17-19 ins) at withers.

Dogs or bitches over or under these specified sizes are undesirable.

FAULTS - Any departure from the foregoing points should be considered a fault and the seriousness with which the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion to its degree.

NOTE - Male animals should have two apparently normal testicles fully descended into the scrotum

HISTORY OF AUSTRALIAN CATTLE DOG AND STUMPY TAIL CATTLE DOG

The Australian Cattle Dog and his cousin, the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog, share common origins in the Halls Heeler, a distinct working-dog breed developed in the 1830s by Thomas Hall. Need drove the development of the Halls Heeler and the early history of both breeds is interlocked with the history of the Hall family and the growth of the Hall cattle empire.

George Hall, with his wife and four young children, arrived in the fourteen-year-old New South Wales Colony in 1802. At first, George was put to work on a Government farm at Toongabbie but in 1803 he was granted 100 acres on the Hawkesbury River, on the north-western fringe of the Colony. George prospered and soon added to his land holdings. By 1820 he owned or rented some 850 acres. George's family also grew. Thomas (1808-1870) was one of six sons and three daughters. |

|

|

|

Thomas Simpson Hall c. 1832.

|

|

Successful exploration during the 1810s discovered rich grazing land to north, west and south of the highlands that surround Sydney. John Howe, a close friend of George Hall, established a useable track from Windsor to the Hunter River in 1819 and in 1824 the younger Halls, including Thomas, explored the Upper Hunter Valley with the intention of selecting land. By 1825 the Halls had established two cattle stations in the Upper Hunter Valley, Gundebri and Dartbrook. Thomas Hall settled at Dartbrook and his home became the base for the northward expansion of the Halls' pastoral interests into the Liverpool Plains, New England and Queensland.

Droving from the Hunter Valley stations to the Sydney meat markets, along John Howe's original track, was difficult because of dense scrub and difficult terrain. Droving from the Liverpool Plains runs to Sydney presented a more acute problem. In droving terms, thousands of head of cattle had to be moved for thousands of kilometres along unfenced stock routes, including through the rugged Liverpool Range. A note, in his own writing, records Thomas Hall's anger at losing 200 head in scrub. |

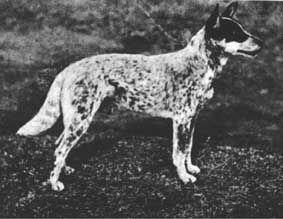

A droving dog was desperately needed but the colony offered nothing suitable. The colonial working dogs are understood to have been of Old English Sheepdog type (commonly referred to as Smithfields), imported from the south of England. Jack, a dog of this type, was photographed at the Metropolitan Intercolonial Exhibition, Sydney, in 1898, where he was exhibited as a Cattle Dog. With their heavy build, shaggy coats and intolerance to climatic and vegetation conditions, the Colonial Smithfields were useful only over short distances and for yard work with domesticated cattle.

Thomas Hall addressed the problem.

For some years, Thomas had kept Dingoes at Dartbrook for study and realised that they had potential in the development of a working dog. He now looked for a second breed to cross with Dingo. Probably on the advice of his parents (both from farming backgrounds), Thomas imported Drovers Dogs from his parents home county, Northumberland. For convenience the Hall family historian, A J Howard, gave these dogs a name: Northumberland Blue Merle Drovers Dog; drovers dog for their function and blue merle for their blue mottled colour. |

|

| Jack, exhibited as a Cattle Dog in 1898. |

|

These Drovers Dogs had long been bred for their working characteristics and distinctive colour by ancestral Halls and other farmers in Northumberland and across the border in Scotland. By the early 1830s, when Thomas Hall imported his Drovers Dogs, these and many other Drovers Dog strains were becoming extinct in Britain. The distinctive blue colour, however, is still to be seen in some modern British working dogs. It is not associated with the Merle gene.

The origins of the Northumberland Blue Merle Drovers Dog are obscure. The short coat, conformation and natural taillessness of the Cur Dog, illustrated by Bewick and other early British writers, suggest that the Cur was one of the ancestors. Some of these early writers describe the Cur as a Drovers Dog. Thomas Hall's imports may, or may not, have been tailless themselves. As possible carriers of taillessness, they are the most likely source of taillessness in the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog. |

| |

| Modern British working-dog. Photo, courtesy David Hancock |

|

|

|

|

| The Cur Dog, from an engraving by Thomas Bewick. |

| |

Thomas Hall crossed his Drovers Dogs with his Dingoes and by 1840 was satisfied with his resultant breed. During the next thirty years, the Halls Heelers, as they became known, did not disperse beyond the Hall properties. The Halls were dependent on the dogs and, given the number and size of the runs needing Halls Heelers, it is unlikely that there was a surplus. Besides, the dogs gave the Hall family an advantage over its competitors in the cattle industry.

After Thomas Hall's death in 1870, the Hall cattle empire came to an end. The runs in northern New South Wales and Queensland went to auction with the stock on them and, for the first time, Halls Heelers became freely available. Some were retained by stockmen from the former Hall properties and others were eager to own them. It is thought, for example, that the stockman, Jack Timmins, acquired his famed Timmins Biters (Halls Heelers) at this time. The wholesale butcher, Alexander Davis, is said to have brought Halls Heelers to Sydney, from the Hunter Valley, to work in his cattle yards and move cattle from yards to abattoir.

By the 1890s, Halls Heelers, by then known simply as Cattle Dogs, had attracted the attention of several Sydney dog breeders with interests in the show ring, of whom the Bagust family (particularly Harry Bagust, c.1860-1914) was the most influential. In 1897, Robert Kaleski (1877-1961) drew up the first Breed Standard for the Cattle Dog. Kaleski's Standard was published by the NSW Department of Agriculture in 1903 and re-published in 1910. From 1903 until his death, Kaleski campaigned tirelessly for true recognition of Australian stock dogs - Cattle Dogs and Kelpies.

Also in the 1890s, Cattle Dogs of Halls Heeler derivation were seen in the kennels of exhibiting Queensland dog breeders such as William Byrne of Booval (near Ipswich). It is thought that these Cattle Dogs were obtained from former Hall properties in southern Queensland and northern New South Wales.

The early exhibited Cattle Dog population in Queensland differed from the parallel population in New South Wales. The Queensland population included both long-tailed and stumpy-tailed types and both types were exhibited in the same classes. Stumpy-tailed exhibits were sufficiently strong in numbers by 1917 for some shows to have introduced separate classes for long-tailed and stumpy-tailed entrants. Queensland also had a marked preference for blue. Stumpy Tail Cattle Dogs appear not to have been exhibited in New South Wales and there is evidence of strong discrimination against them. Red speckled Cattle Dogs were, however, accepted in New South Wales and the Royal Agricultural Society of New South Wales introduced separate classes for them in 1918.

The early Queensland population progressively lost its identity, however, except in the kennels of the few breeders that were dedicated to Stumpy Tail Cattle Dogs. William Byrne (his early breeding included stumpy-tailed Cattle Dogs) is the first Queensland breeder known to have favoured New South Wales bred Cattle Dogs. His first was Rowdy, probably whelped 1899, and others followed during the next twenty years. Byrne may even have set a trend; other breeders certainly followed his lead. The number of Sydney bred dogs found in Brisbane and Ipswich kennels increased during the 1920s and 1930s. They included Little Logic, whelped 1939. There was no corresponding Sydney interest in Queensland-bred dogs until after World War II. Cattle Dogs, known as Australian Heelers or Queensland Heelers, became an exhibited breed in Victoria during the 1930s and Victorian breeders also shopped in Sydney. |

|

|

| Little Logic. |

|

|

| Logic Return. |

|

| |

| Royal Shows were suspended during World War II and resumed in 1947. Sydney exhibitors saw Little Logic offspring, for the first time, among entrants at the Sydney Royal of 1947. These exhibits, and their sires' show record, created immediate demand for Little Logic's lineage. By the end of the 1950s, there were few Australian Cattle Dogs whelped that were not Little Logic descendants. The convergence on Little Logic continued into the next generation when Little Logic's best known son, Logic Return, also attained prominence in the show ring and popularity at stud (initially in Brisbane and later in Sydney). |

|

| |

The prominence of Little Logic and Logic Return in the pedigrees of modern Australian Cattle Dogs was perpetuated by Wooleston Kennels. Whelped in 1965, Wooleston Blue Jack was line bred to Little Logic and Logic Return, and Wooleston Kennels subsequently line bred to Wooleston Blue Jack, himself. For some twenty years, Wooleston supplied foundation and supplementary breeding stock to breeders in Australia, north America and Continental Europe. As a result, Wooleston Blue Jack is ancestral to most, if not all, Australian Cattle Dogs whelped since 1990 in any country.

|

|

|

| Wooleston Blue Jack. |

|

Looking back from a 2000's perspective, Wooleston's most influential client was Tallawong Kennels in Victoria. Starting with Wooleston Blue Jenny, Tallawong line bred to Wooleston and, by the late 1970s operated as a closed kennel, breeding back to its own lineage. No other lineage is as pervasive in the Australian Cattle Dog population of the 2000s as Tallawong and no dog's descent is as strongly expressed in the modern population as Wooleston Blue Jack's, both via Tallawong and independently of that lineage.

The Role and Impact of Robert Kaleski |

|

Robert Kaleski, a younger breeding associate of Harry Bagust, was a tireless advocate and long-term publicist for the Cattle Dog and other Australian working dogs. Without him they would have lacked an effective voice. He was heard frequently, and particularly in Sydney's weekly newspaper, the Sydney Mail, appealing for true recognition of the role that Cattle Dogs and Kelpies had played, and were playing, in Australia's cattle and sheep industries.

In the pages of the Sydney Mail, Kaleski begged the organisers of the Sydney Royal Show to increase the prize money offered to the agricultural breeds, as an incentive to working stockmen to exhibit their dogs. He pointed out that suburban breeders, being unaware of their importance, were likely to lose some of the important working characteristics in the dogs they bred. Some of his comments on the exhibited dogs of the 1920s and 1930s show that he saw evidence that some Sydney breeders were breeding Cattle Dogs of a type that were far removed from the Cattle Dogs of the early 1900s; photographs from the period support his observations. His pleas for higher prize money went unheeded. |

|

|

|

Robert Kaleski (1877-1961).

|

|

Kaleski compiled the first Standard for the Cattle Dog breed in 1897 and had it published, with photographs, by the New South Wales Department of Agriculture in 1903 and 1910.

Nipper, bred by Harry Bagust, appears to be a classical exemplar of the breed that Kaleski described and is probably close to Halls Heeler in type and conformation. Rural Cattle Dogs, photographed in the 1940s and believed to have been bred from Halls Heeler stock, are similar. |

|

|

| Nipper, bred by Harry Bagust in 1899. |

|

| |

|

Kaleski's Standard was taken up by breed clubs in Queensland and New South Wales and re-issued as their own, with local changes. Despite the modifications to Kaleski's Standard and despite Kaleski's own prejudice against red coat colour and taillessness, his Standard was the first great step in establishing the breeds identity.

Kaleski's versions of Breed Origins

Kaleski's Department of Agriculture publications in the 1910s are written with authority and, combined with the photographs that accompanied them, give insight into the early development of the Cattle Dog and the breed type for which he wrote the Standard.

In his later writings, however, Kaleski introduced some contradictory and unlikely assertions. With the passage of time, these have been generally accepted. The most enduring of Kaleski's myths relate to alleged early Dalmatian and Kelpie infusions, said to have been introduced by the Bagusts into the early Cattle Dog breed. These infusions are not referred to in Kaleski's writings until the 1920s and there is no evidence that they occurred in the mainstream early development of the Cattle Dog.

Kaleski was preoccupied by similarities. For example, for him a red Cattle Dog looked more like a Dingo than a blue Cattle Dog did; therefore there was more Dingo in its total make-up. It seems likely that Kaleski sought to explain the Cattle Dogs mottled colouration and tan on legs by similarity to the Dalmatian and Kelpie, respectively. Having done so, he had then to produce reasons for introducing these breeds, and particularly the strange choice of Dalmatian. The genetics of coat colour, alone, make the Dalmatian an extremely unlikely mainstream ancestor of the Australian Cattle Dog.

In 1911 the Cattle Dog would, according to Kaleski, "make any horse or beast lead, and watch his owner's property when the latter was away from it" and would "gallop to the head of a mob and hold it there". A working dog of perfection.

From a functional viewpoint, the alleged Dalmatian infusion (it was first mentioned in the Australian Encyclopaedia in 1926) was "needed" to instill a love of horses and guarding instincts into the breed and the alleged Kelpie infusion was "required" because the Cattle Dog "could not be sent ahead to block or wheel [the mob]". Kaleski's reasons for these infusions were in complete contradiction to his earlier (1911) statements.

In 1935, by which time the Bagusts were long dead, Kaleski re-affirmed both infusions and specifically attributed them to the Bagusts. The Dalmatian and Kelpie myths became increasingly elaborate with time and eventually Kaleski was able to tell us which Dalmatian (he belonged to "one of the Stephens, a very old Sydney legal family") and which Kelpies (black-and-tan dogs, "Maidens dogs, if I remember aright"). Kaleski also mentioned an early Bull Terrier infusion, but not by the Bagusts.

Given Kaleski's self-contradictions and the belated accounts of the alleged Dalmatian and early Kelpie infusions, it is unlikely that either occurred although the Bull Terrier infusion is probable. This was also the opinion of Alan Forbes (Pacific Kennels), who lectured to trainee judges during the 1960s for the RAS Kennel Control, and of Berenice Walters, Wooleston Kennels.

Various other infusions have certainly occurred during the last 100 years, either by accident or by design. The photographic record includes some very atypical Cattle Dogs, and chocolate and cream miscolour in both modern Cattle Dog breeds has been substantiated. Dingo re-infusions are also well known, dating from the early years of the twentieth century to more recent dates.

Despite his lapse in the matter of breed origins, however, it is hard to believe that the Cattle Dog breeds would have endured without the dedication and commitment of Robert Kaleski.

The Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog

The Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog and the Australian Cattle Dog share the same early ancestry (see above). Both breeds were developed from the Halls Heeler and it is thought that Thomas Hall's imported Drovers Dogs carried the gene for taillessness if, indeed, they were not stumpy-tailed themselves. The later development of the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog, however, diverged from that of the Australian Cattle Dog.

Thomas Hall's developmental breeding was carried out on Dartbrook and Hall is understood to have been satisfied with the result by c.1840. No records survive but it is unrealistic to suppose that Hall retained direct and personal control of all later breeding. The size of the properties operated by the Hall family, and their distance from the Sydney markets had driven the development of the Halls Heeler. Similar factors would have persuaded decentralised breeding. It is thought that, after c.1840, the stockmen on the various Hall properties bred their own dogs, with interchange of breeding-stock between one property and another.

As a result of decentralised breeding, the Halls Heeler seems to have developed two strains: those bred on properties in northern New South Wales and Queensland, and those bred in the Upper Hunter Valley (Dartbrook) and further south. It would appear that the incidence of stumpy-tailed Halls Heelers was greater in the northern strain than in the southern strain. Emphasis was on breeding for working ability and stamina and, if the stumpy-tailed Halls Heelers were workers of excellence, their taillessness would have been disregarded.

After Thomas Hall's death in 1870, the Hall cattle empire came to an end. The runs in northern New South Wales and Queensland went to auction with the stock on them. Halls Heelers from the postulated northern (stumpy-tailed) strain were already in Queensland and northern New South Wales, and generally available to stockmen from the early 1870s.

By the 1890s, the Cattle Dog was an exhibited breed in Queensland. Although separate classes were not scheduled at Brisbanes National Agricultural and Industrial Association shows until 1917, it is evident that the earlier Cattle Dog classes attracted both long-tailed and stumpy-tailed entrants, and that some of the entrants were related. In some shows, Stumpy Tail Cattle Dogs comprised 50% of the Cattle Dog entry.

|

| |

| Stumpy Tail Cattle Dogs were evidently taken for granted in Queensland; a stumpy-tailed Cattle Dog illustrated an article on the Cattle Dog in The Courier-mail Dog Book (1938). |

|

|

During the years following World War I, the popularity of the Stumpy Tail Cattle as a benched breed began a decline. The period saw a corresponding increase in the popularity of long-tailed Cattle Dogs with Sydney breeding behind them. A change in the regulations governing litter registrations, during the 1950s, accelerated the decline. By the 1960s, only one registered breeder of Stumpy Tail Cattle Dogs remained: Mrs Iris Heale of Glen Iris Kennels.

By the 1980s, it became apparent that the Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog, as a registered breed, was approaching extinction. In 1988, the Australian National Kennel Council announced the Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog Redevelopment Scheme. The Upgrade Program, subsequently implemented, has been successful in its basic aim: that of preserving the bench breed.

The name of the breed was changed to Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog on 1 January 2002 and in December 2002 the Breed Standards Commission of the Federation Internationale Cynologique accepted the Country of Origin Breed Standard for the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog.

In type, the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog has remained more faithful to the inferred Halls Heeler type, as expressed by Nipper, than has the Australian Cattle Dog. The onus rests with judges and breeders, to ensure that the Stumpy's distinctive type does not degrade.

References

Clark, N R. A DOG CALLED BLUE: the Australian Cattle Dog and the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle

Dog 1840-2000. N R Clark, Sydney, 2003.

Hewson-Fruend, H J. Changes in Australian Cattle Dog Breed Standards and Type, in N R Clark:

A Dog Called Blue, Chapter 10. N R Clark, Sydney, 2003.

Hewson-Fruend, H J. Inheritance of Coat Colour in the Australian Cattle Dog and the Australian

Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog., in N R Clark: A Dog Called Blue, Chapter 12. N R Clark, Sydney, 2003.

Merchant, B M. The Redevelopment of the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog, in N R Clark: A Dog

Called Blue, Chapter 11. N R Clark, Sydney, 2003.

© Noreen R Clark 2003

|

|

Hall family properties. Scale in kilometres. Map, courtesy A J Howard.

|

|